Tommy wanted to join the Navy. It was his father who pointed out that his football would be restricted if he was to serve most of his time on board a ship or even worse in a submarine. So after a rethink he decided on the Army. Signing up was done in Formby in Lancashire, before he was drafted into a Scottish regiment, followed by a border regiment at Carlisle where Tommy spent three months on weapon training. It was fair to say in the first six months of National service the Prescot lad had done more travelling than in his previous 18years.

Next stop was Hythe in Kent, where he was attached to the South Staffordshire regiment. More training followed and a move again, this time to Dimchurch. It did not take long for Tommy to start playing football again. He appeared for his regimental side, playing against other service sides, mainly at the ground of Folkestone Town.

The club who, still kept going through the war, invited him to turn out for them whenever possible, and he made several appearances on the left wing at Cheriton Road. On one such occasion, not only did he assist his adoptive side to an 11-0 victory over the R.A.F. but notched four second half goals in the process.

Once again it was a case of football being a tight knit community Although no one knew it at the time, some of the players who 'guested' for Folkestone, along with Tommy, would have connections with his previous and future clubs.

Henry Wright was a goalkeeper on Derby County's books He would later go into coaching and hold such a post Everton as well as Walsall and Luton, before widening his field and coaching the nat10nal Lebanese side and becoming a member of the Institute of Sport in Patiala.

Harry Ware of Norwich would also turn out for Northampton Town during hostilities. He was to receive chest wounds at Normandy which led to his premature retirement from the game. Dudley Law, also of Norwich, was Wellingborough born, and also turned out regularly, for the Cobblers reserves.

It was July 1944, when the 216th battalion of the South Staffs regiment were called into active duty and sent to Normandy, along with many other regiments. The company made up of 18- and 19-year-old boys saw their first action after a week. The instructions were to take a chateau, near the town of Epron, that was being used by the German Army as a base.

The regiment were informed they were going over the top at 4.10 am the next morning. At the time a lot of the lads thought they were in a Western with comments such as 'Let me at them' or 'just give me a gun, I'll show them'. Tommy sat back and watched, saying nothing, and only speaking when spoken to ... a policy he would adopt for the rest of his life.

'I knew a lot of 1t was bravado, for in the cold light of day when they lay, waiting for the order to go over the top, there were a lot of frightened lads', Tommy remarked.

There was a more than even chance that many of these teenagers had ever left their hometown or village, yet here they were in a foreign country, with a gun in their hand fighting someone they never knew, not knowing if they would ever return to see their families again.

Tommy remembers laying in the field, his gun in his hand, and his head kept down low, waiting for the order. Then at 4.00 am the skies lit up, like a giant bonfire. The battleships on the coast sent a barrage of shells inland towards the German lines This gave the soldiers of the South Staffs a two-pronged disadvantage.

It could give away their positions to German snipers if the sky remained brighter than daylight. After all, the reason they were attacking in the dark was to do so under cover. There was also the chance that some soldiers could be caught by the barrage, something that was later termed 'friendly fire'.

All these thoughts raced through Tommy's mind, until he heard the order, and

'with his fellow soldiers went over the top. He found himself in a cornfield, holding an Anti-Tank gun, remembering his instructions to 'keep low at all times'. His concentration was broken when he felt a hand grab his ankle, he quickly turned to see one of his fellow soldiers laying on the floor, his hand grasping Tommy's ankle tightly.

'What are you doing?', Tommy asked in shocked surprise.

'Don't go without me', he pleaded.

'All right but for goodness sake, keep your head down, or you'll get us both killed.'

The soldiers stayed there until daylight. Then the order came to regroup, and. the soldiers took over the German trenches in the orchard of the chateau, before returning to the coast. Back at base the bravado returned as the lads told tales of what they had achieved and what they had done, until an instruction came from the commanding officer - 'volunteers wanted - to bury the dead'.

Boasting and laughter stopped, with worse news to follow, some 120 of the soldiers were missing, presumed dead. Most were simply inexperienced teenagers who had naively stood up, before being picked off by German snipers. Later it became apparent they should never have been on the front line in the first place.

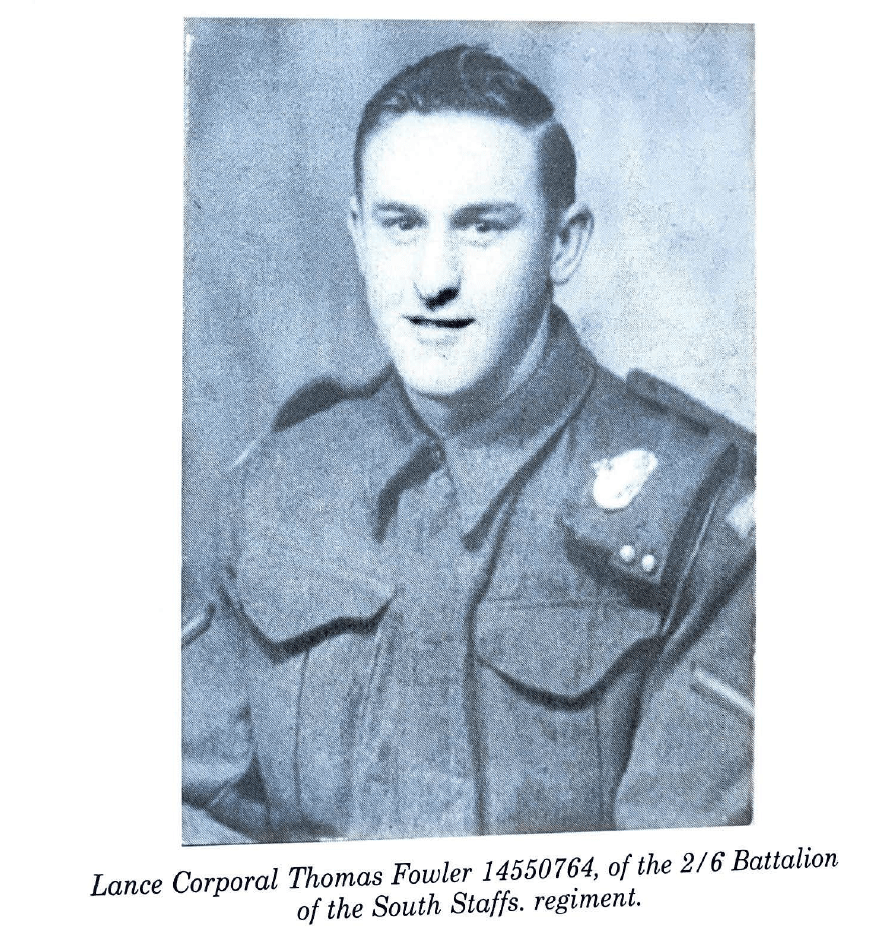

Clearly more experienced soldiers would have minimised casualties, leaving the rookie soldiers for the clearing up operations. The dead were later buried in Canbes-En-Plaine. Tommy often makes the pilgrimage, together with other survivors, to lay wreaths on the graves. After a week's rest the regiment was back in action. By this time, Tommy had won a 'promotion in the field', and he was now a lance corporal. 'I can never remember if I got paid more, but at the time money did not seem so important', Tommy said.

They advanced and found small pockets of foreign troops in hiding. They were mainly White Russians, who were taken prisoner, often wondering if they were going to be shot?. Tommy came across a brand-new belt, and a short bayonet that the Germans used. He decided to keep these as 'spoils of war' and show them to his family on his return home. Within firing distance of the enemy, they dug in and spent a lot of time in the trenches, exchanging fire with the Germans. It was here Tommy found it was not Just the Germans who caused problems, sometimes they came from within. He turned to find a fellow soldier, the same one who had grabbed his ankle in the cornfield, dropping his trousers to answer a call of nature.

'Hey!' spat Tommy. 'You can't do that in here '

'I'm most certainly not going out there to do it', came the reply.

One soldier volunteered to go out and wipe out a sniper who was causing the troops a lot of problems, but he was shot in the stomach, and packed off to the field hospital. Tommy decided to take things into his own hands and went out next.

'I crawled along, slowly, crouching every time I reached something that would give me cover, trying to locate the sniper' Tommy remembered. 'Suddenly, there was a crack of a rifle, and something hit my helmet and spun me around. I felt a trickle of blood running down my face, but did not take a lot of notice, despite being in some pain. I was still alive and had all my senses. Anyway, I wanted to finish the job I had started, even more so now'.

Despite this, he was despatched back to the field hospital, together with the soldier who had suffered the stomach wounds, it was while being carried on a stretcher, with his helmet resting on his chest that he actually saw the two bullet holes in his headgear. It was then he realised a bullet must have gone straight through the helmet, catching his forehead at the same time. . .

He wondered just how bad his injuries were as he was laid on a makeshift bed. A doctor came to examine him, but recoiled away in shock. Tommy was relieved to find this had nothing to do with his wounds, but the hand grenades

still strapped to his tunic. Another disappointment was that his 'finds', the belt and bayonet had been confiscated, although later he realised why. For as he was given a bed in the hospital, he found himself alongside wounded German soldiers as well. Tommy well understood that the war had to stop somewhere ...

It was decided that the wound was bad enough for him to be sent back home. So for Lance Corporal Thomas Fowler 14550764 of the 216th battalion of the South Staffs regiment, the war was over. He spent another two days in the field hospital and then it was back to England in a ship used for landing tanks. The floor was covered in wounded soldiers on stretchers, some without limbs, some blinded, some badly burned, and others like Tommy himself, the walking wounded. It was the most depressing sight that Tommy ever saw in his life.

As they arrived at Southampton docks they were put onto a train and returned to Aldershot barracks, Here those who were active were kitted out with essentials, such as shaving kits. From there it became a merry go round of military hospitals for the young Prescot lad.

First it was off to Blackburn Royal Infirmary, then on to Southport, where all wounded soldiers were dressed out in blue uniforms, another on as South port would play a part in his Cobblers career.

Warrington was the next stop. Here he had a minor operation at least there. was the consolation that it gave him the chance to visit his family in Prescot. Here he met Don Welch. He was a Colour Sargent Major Instructor in the army, But a professional footballer in Civvie street, who play for Charlton Athletic in the 1947 F.A. Cup final against Burnley.

It was here Tommy befriend another young, wounded soldier, who had spent some time in a German prisoner of war camp, He would take him home with him if he had a day, or half day's leave, but the youngster suffered from fits because of his experiences, and often lay on his bed, shouting, sometimes in German, More upsetting was the fact he knew when a fit was about to come on. He would lay on his bed and wait for it to happen.

With constant medical treatment and square meals, Tommy became stronger and it was not long before he started to regain full fitness and his mind turned again to football, although he was still under the supervision of the Army medics.

The chance came at ~is next stop, Kempston near Bedford. It was a convalescent centre for soldiers, where injured servicemen regained full fitness. Tommy met up with two men who were to change his life, Their names were Jack Jennings and Harold Shepherdson Both men helped out at the centre, and both men were to leave their mark in football in years to come.

Jack Jennings was a wing half, playing for Wigan Borough, Cardiff Middlesbrough and Preston. With the latter club he took up coaching, joining Northampton Town, as war broke out in 1939. Despite being over 40 he was pressed into service as an emergency full back, but returned to his first love, coaching. He would later act as coach to the England Amateur team, the British Olympic team of 1960, and became a physiotherapist not only with Northants County cricket team but also the Indian touring team of the 1960's Harold Shepherdson was a centre half with Middlesbrough, guested for Northampton during the war, he finished his days with Southend, before returning to Middlesbrough as trainer, the pinnacle of his career came in 1966, when he trained the England team that won the World cup.

Jack Jennings looked over the new intakes and asked the question; 'Any footballers?'. Two of the servicemen raised their hands. 'And which club do you play for?' There was an element of disbelief, as the coach looked at Tommy, one of the players with his arm aloft. Seeing this small, slight youngster for the first time, His head wound still visible, the answer which followed took some believing. 'Everton!'

Jack Jenning's face was a picture. The other player was a Scotsman named, Archie Garrett. He was to make history for Northampton Town, over the next few years. Archie had started his career at Preston North End but unable to bre3:k into their first team on a regular basis, took the opportunities to return to his homeland, and signed for Hearts. The centre forward was a prolific scorer, but the war interrupted his career and like Tommy he also fell victim to war wounds. Once again fate played a hand.

Kempston was only 20 miles from Northampton, but it was very true but travel between the two points. There was no direct train route, and stopped at every village between, making it near two-hour Journey. The Two players were invited to train with the Cobblers and obviously gave a good account, as they where both picked for the next game, against West Bromwich Albion at the Hawthorns. With travelling so hard, both players were given a weekend pass. They would catch a bus from Bedford on Sunday morning, play the game in the afternoon, stay overnight in Northampton, at the YMCA. Before returning to Kempston on Sunday morning, after a Saturday night at the Salon.

It was a lot of messing about for a game of football, but then Tommy had not played competitively for two years. Even worse, the players were only paid expenses. Tales that manager Tom Smith plied players with eggs and vegetables from his farm were nothing more than a Myth.

'We used to make a little bit on expenses, but it was not much', recalled Tommy. 'Tom Smith would pull a wad of notes out of his pocket after a game and approach each player: 'Expenses? 'Each player would give him a figure, but we weren't silly and each had a good idea how much he should be asking for'. In Tommy's case, it probably just about covered the cost of a few beers at the Salon on a Saturday night.

'The only thing I remember about the game at West Bromwich was someone coming out from the crowd and shaking my hand', Tommy remarked. 'It was someone I had served in France with. He told me he would meet me after the game, but it never happened, and I never saw him again'.

In the Northampton team, that day was goalkeeper Alf Wood, a Coventry City player, who was also training soldiers in unarmed combat. Tom Smalley, the ex-Wolves and England wing-half was at right-back, guesting from Norwich City, while his partner at left-back was Andy Welch, previously with Darlington, Manchester City and Walsall. Gwyn Hughes, one of the half-backs, was the only non-guest in the side. The young Welshman was from the Rugby area, recommended to the club by their ex-goalkeeper Len Hammond who lived in the area. Bill Coley a no-nonsense, hard-tackling ex-Wolves player was Gwyn's wing-half partner At the time he was on the books of Torquay. Between the two, at centre half was Bob Dennison, a physical, bustling centre half from Fulham, although he had previously played for Newcastle United and Nottingham Forest. as a forward.

Jim Brown the Irish international from Grimsby was on the right-wing, Bill Fagan, of Liverpool and Scotland, was his inside forwarding partner. Ironically, when Bill finished with football he became a prison officer at Wellingborough, and his son Gary had a spell on Northampton's books, although he did not play in the first team. His position was ... outside left! Travelling companion Archie Garret was at centre forward, and the inside left position was covered by Alf Morrall, who was based in the Midlands, having only played non-league football. Tommy took up the position he knew best, outside left. The game was a disaster for the Cobblers, who lost 0-6. Andy Welch was injured and had to leave the field, which meant a forward-moving to halfback, as Bill Coley took Welch's position. Then Bob Dennison received a cut on the nose and left the field for a spell. Injuries disorganised the team and add to that the face West Brom were on a run, of five games without defeat, and you had the recipe for a one-sided affair. Ike Clarke hit his eighth wartime hat trick and only a few weeks earlier they had beaten Smethwick 17-0 in a friendly.

All this happened m March 1945 The season was almost over, but even in the few games that Tommy played there were quite a few strange happenings. Like the match against Birmingham where the Cobblers had no centre forward. So they played reserve keeper Alex Lee, hoping his 6' 2" and 14 stone frame would upset the opposing defence. Very often Tom lined up with a player one week, only to find him 1n the opposing side the following week, while players missing trains or connections, were all common occurrences.

Tom managed for games during that season, winning the last one, against Derby, and scorning his first goal for the club. 'That was something I could not get over, my lack of goals at Northampton', The left-winger mused. ''At Everton, I was averaging a goal every other game but here it was nearer one in five.' Around the same time, Tommy has moved again, this time to the 23rd Infantry Holding battalion, stationed in Herefordshire, just outside Ross-on-Wye. He went straight into their football side and helped them to lift the Herefordshire County Cup, that season. Among his teammates was Harry Ware of Norwich, who had played with Tom at Folkestone, and Arthur Cambridge, the ex-Stoke and Port Vale wing half.

There were also a few games for Hereford for the young winger as he strove to bring himself back to peak fitness. 'The war was over by now, and my mind on football, but at the present, I was still in the Army, had time to serve, and that took priority, although they were very good when I was asked to be released for football ' Tommy said.

The first posting was at Foxley, and then a centre just outside Ross on Wye. It was at the latter camp that Tommy found himself an enjoyable little job, He would cycle into Ross and collect the post for the barracks as well as taking _the camp mail to be posted. It was while in Ross that something happened which would change his life ... for the better!